Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) can be an effective means of safeguarding key ecological features, provided they are strategically located. Conversely, if important habitats lie outside the designated zones, MPAs may become counter‑productive, especially when fishing effort is high and displaced effort forces fishing fleets work harder to remain viable.

This underscores the necessity of evaluating each situation individually. Moreover, certain technological innovations can inadvertently exacerbate impacts by reducing efficiency, as highlighted in a 2024 EP STOA study.

Viable solutions therefore involve three complementary actions to accompany any spatial restrictions: reducing overall fishing effort (both in days at sea and the number of licences issued) while simultaneously rebuilding stocks through more selective, low‑impact fishing practices; and concentrating activity within clearly defined permissible zones, leaving other areas off‑limits.

Over time, such an approach is likely to make fishing techniques using passive gears more economically attractive, encouraging their adoption in place of mobile, bottom‑contact gear within MPAs* and thereby enhancing both ecological outcomes and social acceptance.

(*though, excluding any activity from vulnerable marine ecosystems, VMEs, is likely unavoidable).

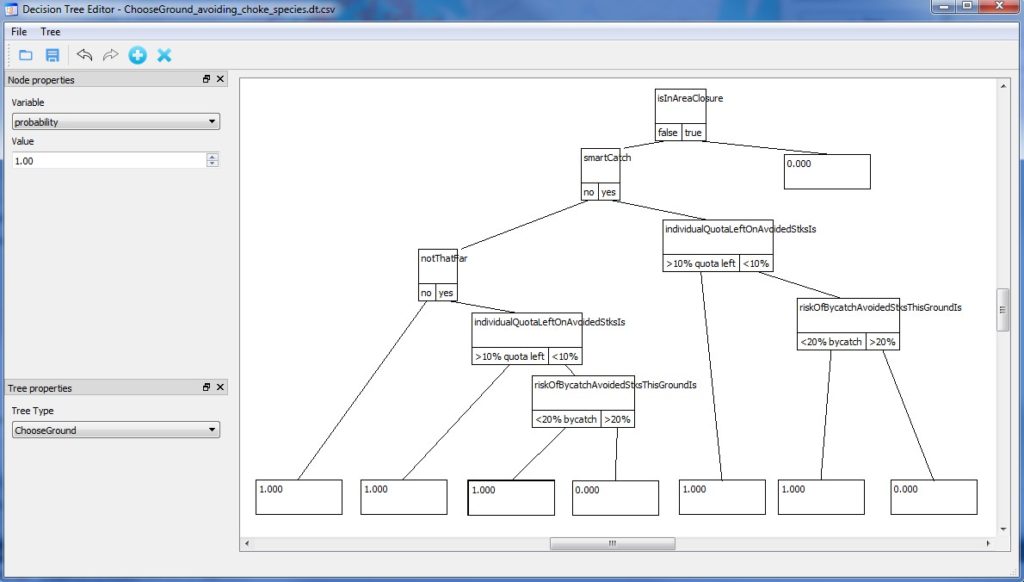

See a paper investigating such issues with modelling tools (published in Frontiers): https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1629180/full